I had been meaning to write about this topic, but Barron’s beat me to it with a terrific article called “Breaking up Tech” which detailed the anti-trust vulnerability of Big Tech companies. The Barron’s article stands in direct contrast to a recent Josh Brown post which postulated that investors are rushing into the technology sector as a hedge against the obsolescence of their own skill sets:

A 45 year old married father of two with a mortgage and a pair of college educations to fund. The remote yet persistent threat of a nuclear war is not what keeps him up at night. In fact, he might almost see it as a relief should it come. He is a bundle of raw nerves, and each day brings even more dread and foreboding than the day before. What’s frying his nerves and impinging on his amygdala all day long is something far scarier, after all. He, like everyone else, is afraid that he doesn’t have a future.

He is petrified by the idea that the skills he’s managed to build throughout the course of his life are already obsolete…

We could be in the midst of the first fear-based investment bubble in American history, with the masses buying in not out of avarice, but from a mentality of abject terror. Robots, software and automation, owned by Capital, are notching new victories over Labor at an ever accelerating rate. It’s gone parabolic in recent years – every industry, every region of the country, and all over the world. It’s thrilling to be a part of if you’re an owner of the robots, the software and the automation. If you’re a part of the capital side of that equation.

If you’re on the other side, however – the losing side – it’s a horror movie in slow motion.

The only way out? Invest in your own destruction. In this context, the FANG stocks are not a gimmick or a fad, they’re a f***ing life raft. Market commentators rhetorically ask aloud what multiple should investors pay to own the technology giants. That’s the wrong question when people feel like they’re drowning.

What multiple would you pay to survive? Grab a raft.

Who is right?

A Big Data world

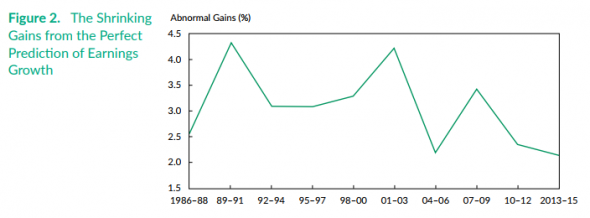

Here is some more flavor on this issue. Consider the fascinating article penned by Feng Gu and Baruch Lev for the Financial Analysts Journal entitled Time to Change Your Investment Model. Gu and Lev found that, even in hypothetical cases where an investor had perfect knowledge of reported earnings, the gains are shrinking very quickly.

Instead, they found that returns to this “earnings surprise” factor was a function of the intensity of intangible assets on the balance sheet. The higher the level of intangibles, the better earnings surprise models performed (assuming perfect foresight).

Here is an example:

Consider a pharmaceutical or biotech company that beats the consensus estimate and/or reports sales growth but has a thin “product pipeline” (drugs or medical devices under development), with no drugs in advanced development, clearly indicating that the good earnings/sales news will be short-lived.

In other words, it’s intellectual property that matters a lot more today than physical property, plant, and equipment. GAAP earnings doesn’t matter as much anymore in a winner-take-all world where intellectual property matters. Think the Big Data companies, or FANG, as prime examples.

Big Data eats the world

It is said that data is eating the world. The one who has the data, wins. Indeed, the dominance of Big Data companies is astonishing. As an example, web advertising is effectively a duopoly, and the dominant companies are reaping monopolistic-like profits.

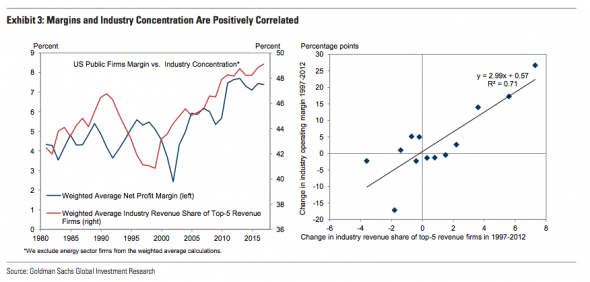

Remember all of the hand wringing over elevated profit margins? Much of that can be attributable to the current winner-take-all environment. Goldman Sachs found that profit margins are positively correlated to industry concentration.

An academic study by Mordecai Kurz at Stanford tells a similar story. IT companies are enjoying monopolistic profits. Here is the abstract:

We show modern information technology (in short IT) is the cause of rising income and wealth inequality since the 1970’s and has contributed to slow growth of wages and decline in the natural rate.

We first study all US firms whose securities trade on public exchanges. Surplus wealth of a firm is the difference between wealth created (equity and debt) and its capital. We show (i) aggregate surplus wealth rose from -$0.59 Trillion in 1974 to $24 Trillion which is 79% of total market value in 2015 and reflects rising monopoly power. The added wealth was created mostly in sectors transformed by IT. Declining or slow growing firms with broadly distributed ownership have been replaced by IT based firms with highly concentrated ownership. Rising fraction of capital has been financed by debt, reaching 78% in 2015.

We explain why IT innovations enable and accelerate the erection of barriers to entry and once erected, IT facilitates maintenance of restraints on competition. These innovations also explain rising size of firms.

We next develop a model where firms have monopoly power. Monopoly surplus is unobservable and we deduce it with three methods, based on surplus wealth, share of labor or share of profits. Share of monopoly surplus rose from zero in early 1980’s to 23% in 2015. This last result is, remarkably, deduced by all three methods. Share of monopoly surplus was also positive during the first, hardware, phase of the IT revolution. It was zero in 1950-1962, reaching 7.3% in 1965 before falling back to zero in 1970. Standard TFP computation is shown to be biased when firms have monopoly power.

It is therefore no mystery as to why FANG stocks have surged. The winners of a winner-take-all competitive environment are reaping the profits of growth and high margins. The secret to Apple’s success isn’t just selling you a phone, or tablet, but to entice you inside their walled garden where they can sell you other products and services. Similarly, Amazon’s strategy is to learn as much as it can about its customers, and sell them more products and services through multiple channels.

These business models show the supremacy of scale in an era of Big Data and AI. Somewhere along the way to market dominance, these companies forgot Google’s original guiding principle: “Don’t be evil.”

The blowback is likely to be fierce. As the latest BAML Fund Manager Survey shows biggest manager overweight is in the technology sector, the blowback will also be painful.

Big Data = Big Brother

John Lanchester, writing in the London Review of Books, worried about the ubiquitous power of Big Data companies and the invasion of privacy. The narrative is quickly turning from “Facebook and Google are innovative” to “Facebook and Google are in the surveillance business”.

What this means is that even more than it is in the advertising business, Facebook is in the surveillance business. Facebook, in fact, is the biggest surveillance-based enterprise in the history of mankind. It knows far, far more about you than the most intrusive government has ever known about its citizens. It’s amazing that people haven’t really understood this about the company. I’ve spent time thinking about Facebook, and the thing I keep coming back to is that its users don’t realise what it is the company does. What Facebook does is watch you, and then use what it knows about you and your behaviour to sell ads. I’m not sure there has ever been a more complete disconnect between what a company says it does – ‘connect’, ‘build communities’ – and the commercial reality. Note that the company’s knowledge about its users isn’t used merely to target ads but to shape the flow of news to them. Since there is so much content posted on the site, the algorithms used to filter and direct that content are the thing that determines what you see: people think their news feed is largely to do with their friends and interests, and it sort of is, with the crucial proviso that it is their friends and interests as mediated by the commercial interests of Facebook. Your eyes are directed towards the place where they are most valuable for Facebook.

The recent ProPublica article about how users could use Facebook to target “Jew haters” was a wake up call for the public. Not only that, the stories about Russian interference in the US election using a Facebook platform doesn’t help matters. I would add that Google has similar targeting capabilities. Bloomberg reported that both Facebook and Google personnel were actively involved in an American led effort to convince voters that France and Germany was being overrun by Sharia law.

In the final weeks of the 2016 election campaign, voters in swing states including Nevada and North Carolina saw ads appear in their Facebook feeds and on Google websites touting a pair of controversial faux-tourism videos, showing France and Germany overrun by Sharia law. French schoolchildren were being trained to fight for the caliphate, jihadi fighters were celebrated at the Arc de Triomphe, and the “Mona Lisa” was covered in a burka…

Unlike Russian efforts to secretly influence the 2016 election via social media, this American-led campaign was aided by direct collaboration with employees of Facebook and Google. They helped target the ads to more efficiently reach the intended audiences, according to internal reports from the ad agency that ran the campaign, as well as five people involved with the efforts.

Facebook advertising salespeople, creative advisers and technical experts competed with sales staff from Alphabet Inc.’s Google for millions in ad dollars from Secure America Now, the conservative, nonprofit advocacy group whose campaign included a mix of anti-Hillary Clinton and anti-Islam messages, the people said.

We are quickly moving toward a Big Brother world where details about anyone is potentially for sale. Consider this CBC report about data vendors in China. The most amazing part of this story is data gathering is not done by the government, but by private companies – and that data is available to anyone at a small price:

There is an entire network — the internet inside China’s Great Firewall — designed to gather the information. And there’s an industry of private and state-owned high-tech enterprises serving it.

“You could go so far as to make the argument that social media and digital technology are actually supporting the regime,” says Ronald Deibert, the director of The Citizen Lab, a group of researchers at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs. They study how information technology affects human and personal rights around the world.

The lab has taken apart popular apps like WeChat, a messaging app that also does financial transactions designed specifically for the Chinese market by private software giant Tencent. It’s used by more than 800 million people here every month — virtually every Chinese person who is online.

Deibert’s team found it contains various hidden means of censorship and surveillance. Among other things, the restrictions follow Chinese students who study abroad.

Chinese authorities “have a wealth of data at their disposal about what individuals are doing at a micro level in ways that they never had before,” Deibert says.

“What the government has managed to do, I think quite successfully, is download the controls to the private sector, to make it incumbent upon them to police their own networks,” he says.

And now it seems, the data these firms collect is for sale.

An investigation by a leading Chinese newspaper, the Guangzhou Southern Metropolis Daily, found that just a little cash could buy incredible amounts of information about almost anyone. Friend or fiancé, business competitor or enemy … no questions asked.

Using just the personal ID number of a colleague, reporters bought detailed data about hotels stayed at, flights and trains taken, border entry and exit records, real estate transactions and bank records. All of them with dates, times and scans of documents (for an extra fee, the seller could provide the names of who the colleague stayed with at hotels and rented apartments).

All confirmed by the colleague. And all for the low price of 700 yuan, or about $140 Cdn.

Stories like this one about how Google’s smart speaker inadvertently recorded every sound that was in the room, even when it was supposedly turned off, raises enormous privacy concerns. The actions of Big Data companies are reminiscent of Lily Tomlin’s Ernestine the operator character from a bygone era (click this link if the video is not visible).

I would add that Amazon isn’t innocent either. Alexa forms part of its Big Data and Big Brother efforts and its smart speakers are the Trojan Horse for consumer AI. As well, Amazon’s patent to prevent shoppers from online price comparison in its own bricks and mortar stores, starting with Whole Foods, is an anti-competitive step to market dominance.

The scapegoats in the next recession

Don’t be surprised when the pitchforks gather at the gates of the Big Data companies in the next recession. Economic pain demands scapegoats. Big Data companies are the perfect candidates. They are not large employers in the United States and therefore they have no natural political constituencies that can stand up on their behalf.

The backlash is already starting. Ben Smith at Buzzfeed wrote that There is Blood in the Water in Silicon Valley:

The tech industry has also benefited for years from its enemies, who it cast — often accurately — as Luddites who genuinely didn’t understand the series of tubes they were ranting about, or protectionist industries that didn’t want the best for consumers. That, too, is over. Opportunists and ideologues have assembled the beginnings of a real coalition against these companies, with a policy core consisting of refugees from Google boss Eric Schmidt’s least favorite think tank unit. Nationalists, accurately, see a consolidation of power over speech and ideas by social liberals and globalists; the left, accurately, sees consolidated corporate power. Those are the ascendant wings of the Republican and Democratic parties, even before Donald Trump sends the occasional spray of bile Jeff Bezos’s way — and his spokeswoman declines, as she did in June, to defend Google against European regulators.

This has led to a kind of Murder on the Orient Express alliance against big tech: Everyone wants to kill them.

The New York Times recently published an article, Silicon Valley is not your friend. As well, CNBC reported that Netflix board member Rich Barton expects an inevitable government crackdown on Amazon:

Technology entrepreneur Rich Barton says government intervention on Amazon in the future is unavoidable.

Barton was asked about his views on Amazon in relation to the Department of Justice’s antitrust investigation of Microsoft during the 1990s in a Bloomberg podcast interview.

“I lived through that DOJ thing. It was really rough. It’s no fun. And I think it is inevitable as companies get really, really huge,” Barton said in the podcast interview published Friday.

“I think Jeff [Bezos] is probably well aware of that,” Barton said. Bezos “is trying to do everything he can to delay that as long as possible and to play within the rules, but eventually the tall poppy gets chopped in

In this era of Big Data, hacking incidents such as the one experienced at Equifax will undoubtedly raise the concerns of some Senate committee in the future. If these Big Data “surveillance” companies know everything about us, what steps are they taking to keep it safe, and what is the extent of their liability should their firewalls be breached?

The Microsoft template

Still, investors should not expect total disaster if Big Data companies face some form of political intervention. Should it occur, the most likely regulatory response would see the breakup of some of the target companies, such as the forced divestiture of AWS from Amazon, and so on, in the same way that the DoJ went after IBM and Microsoft. The Barron’s article went on to raise legitimate antitrust concerns for these companies:

Amazon, Facebook, and Google all benefit from the same sort of network effects that snagged Microsoft. The more people use Facebook, the more others feel they must use it, in a self-perpetuating fashion. Ditto for advertising on Google or selling goods on Amazon. Wall Street and investors may love this virtuous cycle, or, as it’s commonly known, the “flywheel” that keeps expanding their business.

But others, citing Fisher’s work, see exploitation and unfair leverage. They can argue that Amazon sells its Echo home speaker at roughly break-even prices to bring in more shoppers. It’s conceivable such leverage could be interpreted by regulators as predatory. Another example is Amazon’s bundling of its Amazon Prime membership, which offers free shipping and streaming videos, below Amazon’s cost to provide it. Google’s use of Androis to maintain its search engine as pre-eminent on mobile devices has been likened to the kind of “tying” that Microsoft tried with Internet Explorer.

Should the regulator decide to act, my working template is the Microsoft experience. As the chart below shows, MSFT became a market performer after the Justice Department initiation of the United States v. Microsoft Corp.

The path forward

If a political backlash were to occur, the most likely economic backdrop would be a recession. I can suggest a couple of analytical frameworks for investors to deal with the change in environment.

First, Marc Chandler suggested that the current growth problems can be attributable to an abundance of capital:

When farmers have a bountiful crop, and the price threatens to fall below the cost of production, governments often invent schemes to buy the crop and warehouse it and let the agricultural produce come to market at a better (i.e., lucrative) time. In some ways, QE can be understood as a similar strategy: Warehouse the surplus capital. This is not a permanent solution. There is a political push back on the grounds that it blurs monetary and fiscal policy. There is an ideological resistance to the “interference” with market forces. There are economic arguments against the distortion of prices and the mutation of printing signals.

Interest rates are low, not simply because central banks are buying bonds and maintaining large balance sheets by recycling maturing issues. Interest rates are low because there is too much capital. It is a recurring source of the crisis in market economies. We should anticipate that returns to capital will remain low until a new strategy to deal with the surplus is devised and accepted, and the risk is that we are still in denial.

An article in HBR outlined some corporate strategies in an environment characterized by an abundance of capital. Investors should look for companies that make many small bets, and don’t put all your eggs in a single basket:

Strategy in the new age of capital superabundance demands a fundamentally different approach from the traditional models anchored in long-term planning and continual improvement. Companies must lower hurdle rates and relax the other constraints that reflect a bygone era of scarce capital. They should move away from making a few big bets over the course of many years and start making numerous small and varied investments, knowing that not all will pan out. They must learn to quickly spot—and get out of—losing ventures, while aggressively supporting the winners, nurturing them into successful new businesses. This is the path already taken by firms innovating in rapidly evolving markets, but in an era of cheap capital, it will become the dominant model across the business economy. Companies that practice this strategy will have the edge so long as capital remains superabundant—and according to our analysis, that could be the case for the next 20 years or more.

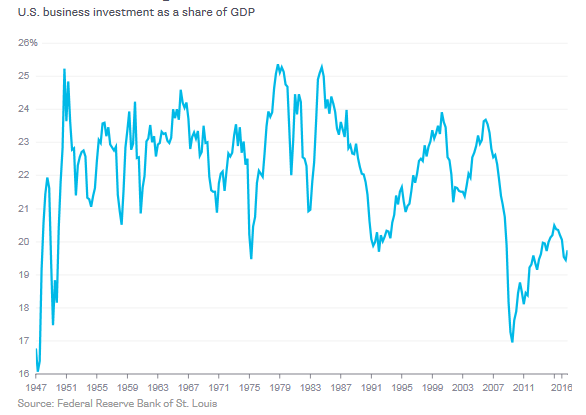

Another effect might see the reversal of the tangible vs. intangible investment rates identified by Gu and Lev as a winner-takes-all environment erodes.

In that case, equity analysis might return to a more conventional framework, where a focus on earnings, and ROI on invested capital matter more to investment returns. In that case, we may see capex intensity return to historical norms.

In that case, a return to higher capex levels as the economy returns to “normal” wouldn’t be such a terrible outcome either.

Hi Cam…that is a VERY interesting article. Thanks for bringing together such a wide range of sources and offering your interpretation.

Time for the aluminum foil hats ?

One of your best – expands the range of scenarios. Being aware of the possibility makes one more aware of the realization should it unfold.

Best article yet Cam. Big tech is just as dominant as the railroads were a hundred years ago. But they have a key advantage over the monopolistic railroads, they know everything about you.