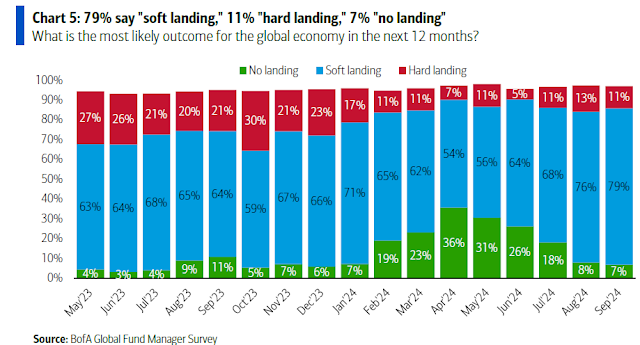

The latest BoA Global Fund Manager Survey shows that a soft landing for the U.S. economy is the overwhelming consensus.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell leaned into that narrative at the post-September FOMC press conference after announcing the rate cut. He characterized the cut as “an appropriate recalibration of our policy stance”. The economy “has continued to expand at a solid pace”. Conditions are not recessionary: “Growth of consumer spending has remained resilient, and investment in equipment and intangibles has picked up from its anemic pace last year”.

Such a scenario should be equity friendly, but presents headwinds for bond prices. What could possibly go wrong?

The bear case

Here is the bear case for the soft-landing scenario. A growing chasm is appearing between the expectations of the bond market and the stock market.

Including the already announced half-point cut, the fixed income market is discounting 2.25% in rate cuts until next September. That’s a pace rarely seen outside of recessions.

Leading indicators of employment, such as temp jobs (blue line) and the quits/layoffs ratio (red line), are weak.

Over in the stock market, bottom-up forward 12-month EPS estimates are expanding at a solid pace. John Butters at FactSet reported that “analysts are projecting earnings growth of 15.2% and revenue growth of 5.9%” for calendar year 2025.

Much of the expected growth may have already been discounted in stock prices. The S&P 500 is trading at a forward P/E of 21.4. That’s considerably higher than the P/E multiple of 15 seen during the last soft landing in 1995–1996.

To be sure, the difference between today’s stock market and the 1995–1996 era is the AI-related boom. But BoA pointed out that “the average EPS growth rate among AI ETF constituents has fallen from 18% to just 5%, below the S&P 500”.

Risk appetite is already elevated, as measured by historically narrow junk bond yield spreads.

The bull case

The bulls will argue that the bears have it all wrong.

The yield curve has normalized and disinverted, which is the bond market’s signal of a growth acceleration. While past normalization episodes have preceded recessions, current conditions are economically similar to the soft landing of 1995–1996.

While economic growth has decelerated, there are few signs of recession on the horizon. As Fed Chair Powell observed at the press conference, “GDP rose at an annual rate of 2.2 percent in the first half of the year, and available data point to a roughly similar pace of growth this quarter”. The current reading of the Atlanta Fed’s Q3 GDPNow is 2.9%, which is well above the pace cited by Powell.

What’s more, productivity is strong, which is supportive of non-inflationary growth.

From a technical perspective, market breadth is still bullish. The S&P 500 and NYSE Advance-Decline Lines reached all-time highs. Bear markets simply don’t behave this way.

Lastly, whoever wins the election in November, investors should see a growth supportive expansionary fiscal policy. Neither party has been strong advocates of austerity.

The verdict

What’s the verdict? Is the glass half full or half empty?

I believe conditions are supportive of a soft landing. Investors need to distinguish between stock market direction and the magnitude of the move. Economic and price momentum determine direction, which is up. Valuations determine the magnitude of the move. Investors should expect the equity bull to continue, but the magnitude of the upswing is likely to be subpar due to stretched valuation and risk appetite.

The “recalibration” thesis has to do with normalization of a strong post Covid money expansion led inflation. This was a factor (expansion of money supply) that needed to be controlled quickly. I am not aware when was the last time this happened outside of 1920 flu pandemic. So, such analogues may be difficult to find. The only one analogue that comes close is the 1984 time frame IMHO. The post 1980-82 Arthur Burns inflation led to an era that may be similar to what we are seeing.

The graph above (FRED; Quit rate, temp jobs, all jobs), is now gravitating down to time averaged means.

Cam has elegantly shown in his earlier post the tightness of money supply (based on Fed Funds rate – Core CPI). He has suggested that such tight money supply needs to be normalized and that is what we are seeing based on the recent 50 bps cuts.

Healthy EPS growth of S&P 500, GDP now data, unemployment rate of lower than 4.5% and its slow rate of rise all suggest a recession is not in the pipeline.

Junk bond spreads should widen too if a recession is in the pipeline and that is not happening either.

The torrid double digit gains of the past year or two of S&P 500 may slow down, but even that slowdown seems improbable as post election rally seems to be highly likely. The expanded PE ratios seen currently is discounting this possibility.

All in all, the post 1984 analogue seems increasingly the best fit.

Until recently, high dividend stocks and ETFs had done poorly since the Fed started fighting high inflation in 2022. Now the Utility Index is the leading sector. Makes sense. They will do better as rates fall. The safety of which to own is based on how sensitive companies are to a recession. In a normal recession, people still pay their phone and electrical bill.

Yardeni just raised his probability of a tech led melt up from 20% to 30%. It could certainly happen with the economic and rate outlook favorable. But which is more certain to make a less risky decent return from now to after the election, Tech or High Dividend Payers?

The net savings has been in a downtrend for 70 years. It went negative during the GFC and is negative again. Debt is way too high. The gov’t can print but we cannot. With over 1 Trillion in CC debt, how much relief does even going to zero do. Remember 70-80% of the economy is service. The collision of high debt and negative savings is BAD!

What will happen in the short run, no idea other than the usual Fiat currency endgame which is print print print. So we may see a strong consumer with growing nominal spending, but who will want to hold dollars?

If the Fed buys the bonds they can keep rates low like they did in Japan, but Japan had a positive balance of trade, not negative 1 trillion a year.

It’s gonna be messy.

Time to pull out my Rogoff and Rheingold (if I spelled it right). Apparently inflationary depressions are a common form.

But this can chase money into equities because the companies usually have a tangible value.