This week saw the two examples of the triumph of populism. The Italian election saw the rise the Five Star Movement and Lega Nord, otherwise known as the Northern League. Both are Euroskeptic parties and Lega Nord has an anti-immigrant bias. Meanwhile in Washington, the news of the steel and aluminum tariffs put Trump’s America First policies front and center.

These instances of rising populism present a long-term development economic policy challenge for global elites.

Italian populism explained

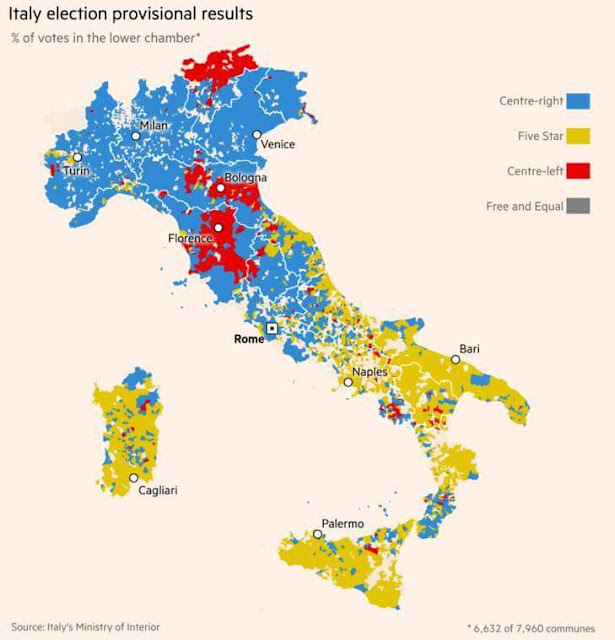

As the electoral map shows, Five Star derives most of its strength from Italy’s poorer south, and Sardinia. One way of interpreting the vote is disillusionment with the European experiment and the ways that the less privileged have been left behind.

We can see a direct inverse relationship between regional GDP per capita and Five Star support.

The Grand Plan teeters

Back in 2012, Mario Draghi revealed the Grand Plan in a WSJ interview. The European Central Bank (ECB) would do its best to hold things together while member states restructured to create more flexible labor markets. In the interview, Draghi distinguished between good austerity and bad austerity.

WSJ: Austerity means different things, what’s good and what’s bad austerity?

Draghi: In the European context tax rates are high and government expenditure is focused on current expenditure. A “good” consolidation is one where taxes are lower and the lower government expenditure is on infrastructures and other investments.

WSJ: Bad austerity?

Draghi: The bad consolidation is actually the easier one to get, because one could produce good numbers by raising taxes and cutting capital expenditure, which is much easier to do than cutting current expenditure. That’s the easy way in a sense, but it’s not a good way. It depresses potential growth.

After austerity comes structural reform “because the short-term contraction will be succeeded by long-term sustainable growth only if these reforms are in place”.

WSJ: Which do you think are the most important structural reforms?

Draghi: In Europe first is the product and services markets reform. And the second is the labour market reform which takes different shapes in different countries. In some of them one has to make labour markets more flexible and also fairer than they are today. In these countries there is a dual labour market: highly flexible for the young part of the population where labour contracts are three-month, six-month contracts that may be renewed for years. The same labour market is highly inflexible for the protected part of the population where salaries follow seniority rather than productivity. In a sense labour markets at the present time are unfair in such a setting because they put all the weight of flexibility on the young part of the population…

WSJ: Do you think Europe will become less of the social model that has defined it?

Draghi: The European social model has already gone when we see the youth unemployment rates prevailing in some countries. These reforms are necessary to increase employment, especially youth employment, and therefore expenditure and consumption.

WSJ: Job for life…

Draghi: You know there was a time when (economist) Rudi Dornbusch used to say that the Europeans are so rich they can afford to pay everybody for not working. That’s gone.

While the ECB did uphold its end of the bargain, structural reform efforts were too slow and uneven. The rise of populist movements like Five Star are the result of those failures. Today, the budgets of every eurozone member state conforms to the 3% deficit limit specified by the Growth and Stupidity Stability Pact.

Today, Angela Merkel has cobbled together a coalition government and she has a governing mandate again. Emmanuel Macron, a pro-European president, is in the Élysée Palace. The window of opportunity for greater European integration to create further shock absorbers for the next downturn is very narrow.

This is the biggest challenge facing the European Establishment. If they fail, the Le Pens and other Euroskeptics are likely to gain further strength in the next recession, and put the European Project at risk.

Populism in America

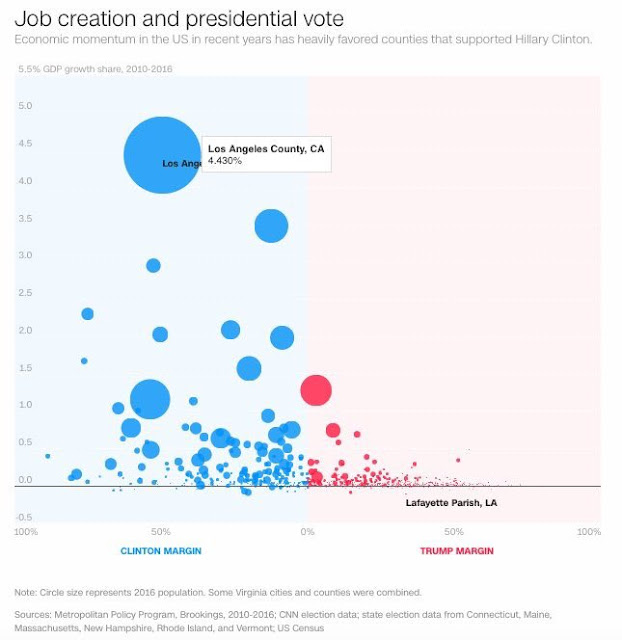

Across the Atlantic, a similar parallel can be found in the last American election. While the relationship is less direct, the inverse relationship between job creation and the Clinton/Trump divide bears an eerie resemblance to the inverse relationship between GDP per capita and Five Star support.

The policy challenge

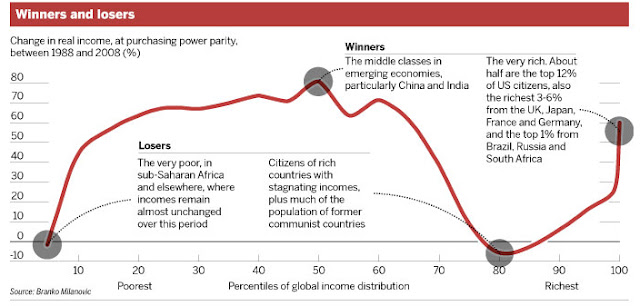

Call it what you want. Protest vote. Disillusionment. These are all manifestations of the “elephant graph” popularized by Branko Milanovic. The winners of 20 years of globalization since 1988 are the emerging market middle class, which is mostly Chinese, and the very rich, who profited from lower costs of production from globalization. The biggest losers were the middle class of the developed economies, who fell behind in real terms as jobs were offshored. They became the constituency for populist movements, such as Trump, Le Pen, Five Star, and so on.

Ray Dalio of Bridgewater recently fretted about what might happen in the next downturn because of the rising divide between rich and poor:

What is Different?

There are two important differences that concern me. They are that 1) there is such a big gap between the haves and the have-nots (which creates social and political sensitivities) and 2) the powers of central banks to reverse contractions are more limited than they have ever been (because interest rates are so low and QE is less effective). For these reasons, I worry about what the next economic downturn will be like, though it is unlikely to come soon.

This presents a unique development economic challenge for the global elites. If the income gap between the haves and have-nots are not closed soon, or sufficient fiscal and other shock absorbers are not put in place before the next downturn, the social environment is likely to turn ugly.

Otherwise, the level of economic, political, and asset price volatility in the next global downturn and recovery are going to be highly elevated by historical standards.