Sometimes misunderstandings can lead to enormous adverse consequences. In 1941, Japan believed that war was inevitable with the United States. The Americans had slapped a trade embargo on Japan, and made it clear that Japanese occupation of China was unacceptable. The Japanese High Command saw that America was a big industrialized country with resources that it could not defeat in the long run. The only solution was a quick strike to destroy American combat capabilities. The logical solution was a sneak attack on Pearl Harbor as a way of crippling American naval power. The rest, as they say, is history.

Tokyo just had one fatal misinterpretation of the American position. Washington did not consider Manchuria, which was China’s industrial heartland and the jewel of Japan’s occupation of the Chinese mainland, to be part of China. Had Japan withdrawn its troops from the south and remained in Manchuria, American entry into the Second World War would have been delayed for several years. Under that scenario, Nazi Germany would not have been forced to fight a two front war. Britain and her Commonwealth Allies would have been too weak to land in Italy in 1943, and the D-Day landings would have been out of the question. There would have been no Manhattan Project, or it would have been delayed for several years. Hitler might have been able to develop the Bomb. History could have been dramatically changed,

A similar scenario is setting up in Sino-American relations. Both sides seem to be talking past each other. The result could be a trade war with catastrophic results (see Could a Trump trade war spark a bear market?).

A belligerent America

The first shot was fired this week when the Trump administration slapped tariffs on Chinese solar cell manufacturers and Korean washing machines (see press release). Bloomberg also reported that the Commerce Department submitted a report to the White House that could lead to tariffs on Chinese aluminum. A similar report on Chinese steel is also due imminently. A Reuters article described how Trump is considering retaliation over Chinese intellectual property theft.

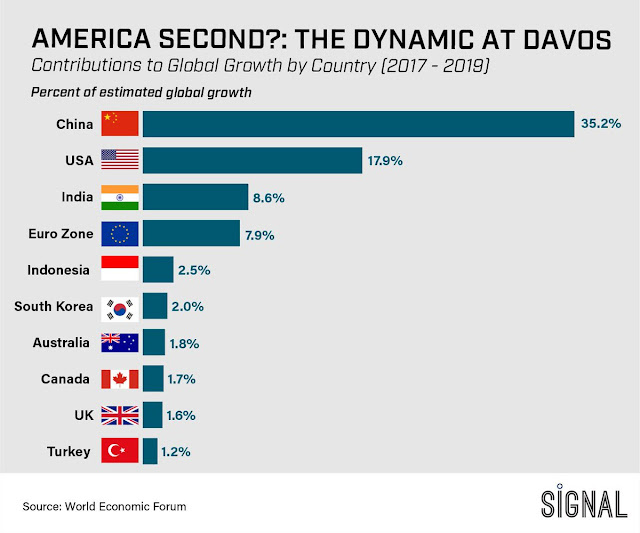

In addition, Trump will be at WEF in Davos, where he is expected to make an aggressive “America First” speech on trade. Observations like this one are likely to raise his level of belligerence.

China miscalculates

Underlying this potential trade conflict is a miscalculation by Beijing that these tensions can be dealt with using the same old tools. Consider this Reuters report entitled China looks to call bluff on Trump trade action:

As influential voices within the U.S. business community warn China that U.S. President Donald Trump is serious about tough action over Beijing’s trade practices, there is little sense of a crisis in the Chinese capital, where officials think he is bluffing.

In Beijing, many experts think Washington is unwilling to pay the heavy economic price needed to upset prevailing trade dynamics between the world’s two largest economies…

People in the U.S. business community say this growing gulf in expectations between Washington and Beijing is fueled in part by the dwindling frequency of talks on commercial issues. The resulting vacuum could set the two governments on a collision course over trade.

China has seen these threats before, and they can be dealt with using the standard negotiation tools:

Beijing suspects that even if Trump implements “targeted tariffs,” as some in the U.S. tech sector expect, they would likely amount to just a few percentage points of the more than $600 billion annual goods and services trade, Chinese experts have said.

For local governments in export-dependent areas, the threat is more worrying. One official in the export powerhouse of Zhejiang province expressed concern to Reuters about Trump’s possible actions, but declined to speak on the record.

The government in Beijing, however, remains stoic.

“Are Chinese officials getting nervous now amid a coming U.S.-China trade war? I don’t think so,” said Wang Jiangyu, a trade expert at the National University of Singapore.

The country has negotiated its way out of previous Section 301 investigations, including in 1992 and 1995.

And a person close to China’s Commerce Ministry, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter, said tariffs from the Section 301 case would be self-defeating, and urged negotiation instead.

“We should sit down and discuss this. If their demands are reasonable, we don’t want to go to the WTO,” the person said.

That inclination to fall back on talks and the WTO to resolve frictions may be China’s miscalculation this time, people in the U.S. business community say.

Moreover, the Chinese are used to an emphasis on personal relationships and back channels to smooth tensions (see the New Yorker article Jared Kushner is China’s Trump Card). China believes that “state plus” receptions, such as the one Trump received in Beijing, can serve to flatter Trump and enhance relations. Moreover, it can send the likes of Jack Ma of Alibaba to the US and promise a million jobs as a way of easing trade tensions (via Bloomberg).

America’s strategic pivot

Beijing’s miscalculation lays in a basic misunderstanding of Trump’s resolve. Trump’s conviction about unfair trade is part of his DNA, and nothing will move him off that belief. Now that he has achieved his main Republican priority of a major tax cut in his first year, expect Trump to be more Trump in trade policy.

Moreover, the newly released National Security Strategy of 2017 (NSS) refocuses and redefines America’s approach to foreign policy and trade. Economic security is now national security. China is now a strategic competitor. These views are not the results of midnight tweets, but a policy statement developed by staff within the Trump administration.

Daniel Rosen summed up the latest NSS this way:

While the competitive aspect of the US-China relationship has been creeping up for years, what really created foreboding at the end of 2017 was the connection of economic affairs to the China national security equation in the NSS. The Strategy suggests that hundreds of billions of dollars of commercial technology are nefariously conveyed to China every year, taking advantage of the permissive US attitude in the economic relationship. The strategy pledges to end this, and this line is already evident in policy: trade actions against imports, action to make investment screening stricter, and disengagement from government to government dialogues are happening, now. President Trump will tie these threads together (and likely add to them) in his State of the Union address January 30.

So to sum up what has changed:

- China: No longer maintains ambiguity about the nature of the Chinese system and whether it will converge with OECD norms: it emphasizes the differentness and says it won’t.

- The US: Now defines China as a strategic competitor, not a transitional nation converging with our norms, and sees economic dynamics as core to this competition: engagement is now a verb – sometimes the right action – not a noun describing policy.

Rosen went on to outline the implications of this policy pivot:

Some consequences of a strategic shift are already evident. Of four bilateral dialogues President Trump kicked-off at Mar-a-Lago, three are frozen (economics, law-enforcement, and people-to-people: only the military-to-military channel is still operational, largely on the topic of North Korea). Dozens of agency-to-agency channels of engagement set up over the past decades are in hiatus. Very few American officials are visiting China. China is not alone in this regard, but the US-China bilateral agenda is more important that virtually any other. This reduces the channels for managing and delivering solutions on the broad spectrum of bilateral issues in the future.

The strategic redirection means stepped-up trade and investment confrontation. It remains unclear whether US economic policy will be tailored and specific, or very broad. Tailored looks like high dumping duties on specific types of steel and aluminum products; broad means arguments such as that Chinese capital costs, energy prices, land rents, intellectual property costs and other fundamentals are all inherently subsidized, and should be countervailed by high duties on virtually anything shipped from China (including goods from US firms in China).

Likewise on the direct investment (FDI) front, the US could reasonably step-up screening for truly security-relevant concerns and yet still leave plenty of room for a multifold rise in inflows (this is essentially current policy); or, it could go beyond narrowly security-oriented issues and make it hard for Chinese investors to do even basic deals in mature industries. That would satisfy the US appetite for “reciprocity”, but it might not do the US any good.

How any of this plays out, no one knows:

Where on the spectrum these US policies come out in practice over the coming months will make all the difference. Steps by Beijing to compromise may yet help mitigate the outcome, although so far there is little indication that this is in train. China will of course retaliate, to different degrees depending on the breadth of US actions and its own strategic analysis.

A recent New Yorker article pointed out that Sino-American competition is not just on trade, but in military terms:

The Defense Department is trying to change that, an effort reflected in its latest National Defense Strategy. Syntactically, the document is fairly straightforward: the Pentagon wants more money to buy more stuff. But the type of war it plans to fight is novel. In short, the Pentagon is trying to move on from the war on terror. “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security,” the strategy, which is being released later today, reads. China and Russia are now America’s “principal priorities.”

The DoD is sounding the alarm about how American military forces are configured to fight small wars, much in the same way that British forces were configured for small counter-insurgency conflicts such as the Boer War early in the 20th Century when it was caught offside when it entered the First World War:

Some Defense officials see the continued focus on post-9/11 foreign interventions as problematic over the long term. While hundreds of thousands of Americans were fighting religious zealots in the desert, the Chinese and Russians were building new rockets and satellites. “There’s always an opportunity cost. The forty-five billion that we’re spending a year in Syria and Afghanistan would fill a lot of holes in our arsenal,” the senior Defense official said. “A professional boxer who trains against lesser opponents doesn’t improve.”

Doug Wise, a former C.I.A. paramilitary and operations officer who served in the Middle East before becoming the deputy director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, said counterterrorism missions were critical, but came with a cost. The deaths caused by suicide bombers and maniacs who shoot up night clubs were “terrible tragedies,” he said, but, in the end, “Can ISIS destroy the American way of life? Probably not.” He went on, “You want to talk about an existential threat? How about China’s hypersonic glide missile, which can travel at multiple times the speed of sound and could take out an aircraft carrier before you could even blink? If the entire Pacific Fleet was at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, that would pose an existential threat.”

As China has become more powerful, she has become more assertive in her foreign policy. The latest NSS of 2017 is heightening the risk of a military conflict in the South China Sea.

Risks are rising

Davos attendees were polled on changes in risk levels in 2018 compared to 2017. The biggest increase came from the category of “political or economic confrontations/friction between major powers”. The second was “state on state military conflict or incursion”.

For now, the markets appear to shrugging off these protectionist threats. I wrote about some of the likely consequences of a trade war (see Could a Trump trade war spark a bear market?). When does the market start to discount these concerns?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

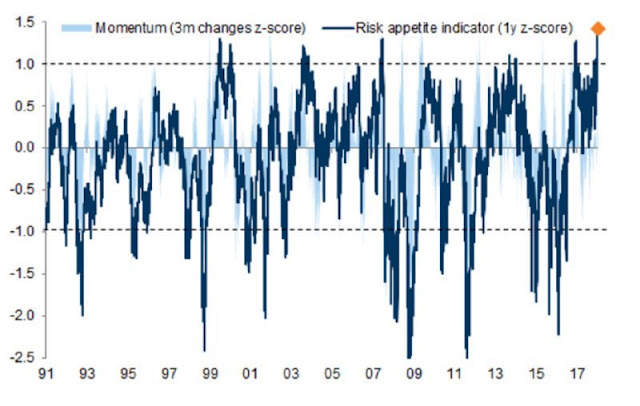

Tactically, these risks have a way of not mattering until they matter, especially in an environment dominated by price momentum. The Goldman Sachs Risk Barometer has now risen to a record level that exceeds the market highs seen in 2000 and 2007.

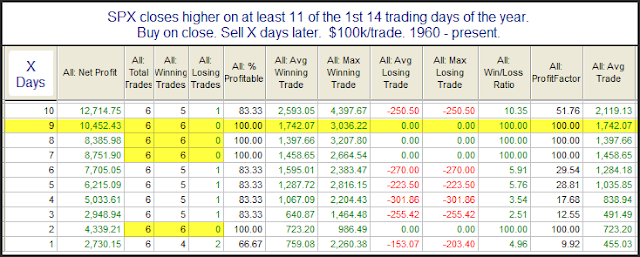

Rob Hanna at Quantifiable Edges discovered six instances since 1960 where momentum has been this powerful. He found that prices have continued to rise, but with the sample size this small (N=6), and only a single episode in the last 30 years, he concluded that the study “make me a little more wary of trying to short into this strength”.

Tactically, traders would be best served by waiting for the downside break before getting overly bearish.

It doesn’t make me feel any better about the markets when Robert Shiller voices a warning at Davos about the stock market crash not needing a catalyst.

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2018/01/23/cohn-trump-wants-everyone-in-davos-to-understand-what-hes-accomplished.html

Sorry, wrong link. Here is Shiller’s interview.

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/01/23/markets-could-suddenly-turn-and-they-dont-even-need-a-trigger-nobel-winning-economist-shiller-says.html