Inadequate models of inflation

Key differences

Here are some key differences between today and the 1970s era of runaway inflation.

In the 1970s, the Fed allowed inflationary expectations to run out of control. That’s not the case today. Even though the breakeven rate has edged up a little, market-based measures of inflationary expectations are well-anchored. To be sure, levels are slightly above the Fed’s 2% target, but readings don’t show any signs of acceleration.

Rising inflationary expectations led to a cycle of both cost-push and demand-pull inflation. Fed Chair Paul Volcker broke the cycle with a painful regime of high interest rates (red line) that tamed rising price expectations and wage increases (blue line).

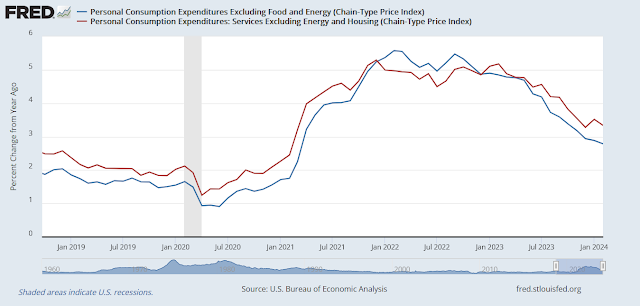

When we consider the inflation picture today, core PCE is falling, but core services is stubbornly high.

Further analysis shows that shelter and transportation costs are the key drivers of inflation in 2024. As BLS shelter inflation indicators operate with a lag, it is also known that real-time estimates of rent and shelter inflation are falling rapidly.

If the investment narrative today is “higher for longer”, the longer-term view is “longer doesn’t mean forever”. Rate cuts will eventually be necessary. Indeed, the market is now discounting the first Fed cut to occur at the September FOMC meeting.

An era of fiscal dominance

That said, we live in an era of fiscal dominance, or high fiscal deficits. The IMF recently issued a warning about the sustainability of fiscal deficits in the U.S. and China.

As the U.S. is undergoing an election this year, the IMF observed that spending tends to be more expansionary in election years, which worsens the deficit.

Lisa Abramowicz at Bloomberg reported that Morgan Stanley expects greater fiscal deficits regardless of whether the Democrats or Republicans win the election, though each party will plot its own fiscal path. That sounds about right.

The problem remains the U.S. will need to refinance about 40% of its total debt of $34.5 trillion in the next three years. However, the problem doesn’t appear to be dire. The IMF is projecting U.S. interest payments will be stable as a percentage of GDP out to 2029.

A matter of expectations

In effect, rising yields would put considerable strain on the federal budget. Much depends on the bond market’s expectations of inflation and interest rates.

In conclusion, fears of a repeat of the 1970s inflation cycle are overblown. Inflationary expectations are well anchored and the pace wage increases are decelerating. However, the IMF has warned of the risks of the deteriorating U.S. fiscal picture and investors have to acknowledge that we are in an age of fiscal dominance.

Excellent article. The 5 X 5 inflation expectation graph tells everything. Inflation remains grounded.

For bond investors, next few years is a good time to keep maturities short.

For stock investors, 5-15% pull backs are good entry points for new money to be put to work.

What I don’t see is how the deficit will stop growing, and the associated debt burden which is self reinforcing the deficits.

If interest rates stay at 5% then almost all equities will be bought on a growth speculation because few companies are paying 5% dividends.

Of course there is the problem of dollar debasement which I don’t think is going away until the dollar is broken and we are not anywhere near there yet.

The only thing I am really confident about is deficits will continue to increase.