Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model to look for changes in direction of the main Trend Model signal. A bullish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “sell” signal. Conversely, a bearish Trend Model signal that gets less bearish is a trading “buy” signal. The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. Past trading of the trading model has shown turnover rates of about 200% per month.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Risk-on

- Trading model: Bearish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers will also receive email notices of any changes in my trading portfolio.

How the market could crash

At the end of 2016, WSJ reporter Greg Zuckerman made a tweet with ominous implications. Hmm…what happened in 1929?

Here is how a market crash can happen. Donald Trump’s appointment of Peter Navarro, the author of Death by China, represents the biggest source of policy tail-risk for the capital markets. Bashing China may be satisfying for Trump supporters, but the Chinese economy is increasingly fragile (see How much ‘runway’ does China have left?). Impose tariffs on Chinese goods, and you risk a Chinese economic slowdown that drags the world into a synchronized global recession.

While a crash is most definitely not my base case, the scenario of collapsing trade flows from a Chinese hard landing would first tank the Asian economies, followed by Europe, whose banking system are still over-levered and have not fully recovered from the Great Financial Crisis. Under such circumstances, an equity bear market would be a 100% certainty, and a market crash would be within the realm of possibility.

It’s hard to estimate the actual probability of a US induced China hard landing scenario. However, we should get better clarity as the Trump team moves into the West Wing of the White House in the coming weeks. In addition, President-Elect Trump may give us some clues on trade when he holds his press conference on Wednesday.

Fragile China

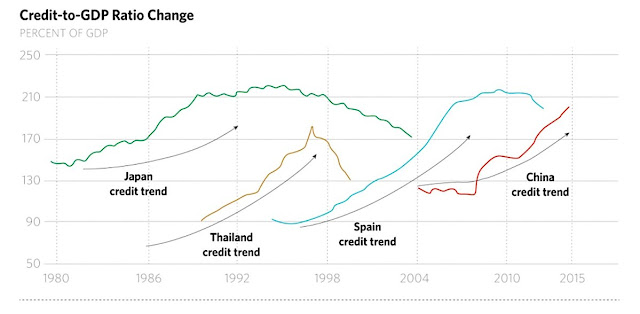

The chart below (via Stratfor) shows the trajectory of credit to GDP of countries that have experienced a strong rise in debt. It is only a matter of time that China’s debt capacity hits the wall, just like every country that has experienced a period of hyper-growth in the 20th and 21st Century.

I wrote a post last summer that highlighted analysis from China watcher Michael Pettis. Pettis made the case that China had a maximum of 2-3 years to resolve its growing debt problem (see How much ‘runway’ does China have left?). Fast forward to today, the time horizon is only 1-2 years.

Christopher Balding, writing in Bloomberg Views, explained the fragility of China’s financial system this way:

Rising asset prices in China have helped prop up everything from coal and steel firms to consumer sentiment. But with potential bubbles popping up everywhere, the government seems to be laying the groundwork for reform. That could mean raising interest rates, applying new restrictions on trading or tightening other regulations. Remember that such measures, however necessary, carry risks of their own. For example, given that China has some of the world’s most expensive housing relative to income, and extremely low turnover, withdrawing credit could result in a real-estate price shock. That might cause indebted developers to fail, or lead to much stronger government action to prevent a hard landing. As regulators try to rein in other asset prices, watch for similar turmoil in bonds and the yuan.

In short, it’s an accident waiting to happen:

Remember that risk is probabilistic and not mechanistic. As China’s known risks accumulate, the probability of some unexpected event having an outsized impact also increases. In such circumstances, the biggest mistake one can make is to rely on past assumptions to predict the future.

To be sure, most of the Chinese debt is denominated in RMB and therefore any blow-up is unlikely to resolve itself in a typical EM debt crisis fashion. Nevertheless, the cracks are starting to appear. A recent FT article warned of the risks in the Chinese financial system:

The dangerous nexus between shadow lenders and large, systemically important commercial banks. Trusts raise funds for their loans by selling high-yielding wealth management products [WMPs] to investors. For the riskiest trust products, banks typically serve only as sales agents but bear no legal responsibility for product payouts.

Yet investors often ignore these technicalities, assuming that state-owned banks — and by implication, the government — stand behind the products they distribute. Adding to the perception that defaults are impossible is a history of bailouts of WMPs by banks, even where no legal responsibility exists.

In December, the Chinese bond market tanked. It wasn’t just the prospect of the Fed raising interest rates, but shenanigans in the local shadow banking system (via Caixin):

It all started with a rumor that proved true. A midsize brokerage firm, Sealand Securities, was said to be reneging on a deal involving bonds worth originally 10 billion yuan ($1.44 billion) on Dec. 14. It soon turned out that it had made similar under-the-table repurchase agreements with more than 20 financial institutions to buy back bonds worth more than 20 billion yuan. Because those bonds were now trading at a loss, Sealand did not want to complete the agreements and buy them back. And what made it think it could do that? Because it said the seal used for all the repurchase agreements was forged. This had a far-reaching impact on the bond market, regardless whether a firm was directly involved in the troubled agreements or not. Sealand later said it had solved the disputes with the financial institutions after the direct intervention of high-level securities regulatory officials.

The possible default by a midsize brokerage firm sparked panic as it raised the possibility of a bank run in the shadow banking system:

To understand what this means, let’s first take a look at how funds flowed from banks to non-bank financial institutions and the bond market.

Typically, the process would start with a big bank purchasing the wealth management products offered by a smaller bank. The small bank then outsources the investment of the fund it received to a non-financial institution, such as a securities firm. The securities firm invests the money into bonds. But when bond prices kept falling, combined with the pressure of tightened liquidity that banks now need to grapple with, the flow of funds went into reverse as banks wanted cash.

This set in motion events that reinforced one another and increased the bond market volatility. As the securities firm sells off bonds to pay back the small bank, which itself may be facing increased pressure of returning funds to the large bank, bond prices fall further and more banks want their money back.

The December episode was only a hiccup, but where there’s smoke, there’s probably fire.

Enter Peter “Death by China” Navarro

Trump’s appointment of Peter Navarro as the director of the US National Trade Council and Robert Lightizer as US Trade Representative are ominous signs for the Sino-American trade relationship. While on the campaign trail, candidate Trump had shown an antipathy towards China and Mexico on trade. The appointment of Navarro, who authored Death by China, is especially unsettling. Lightizer has spent much of his career representing American steel producers in trade dispute litigation and he is unlikely to be any friend of China.

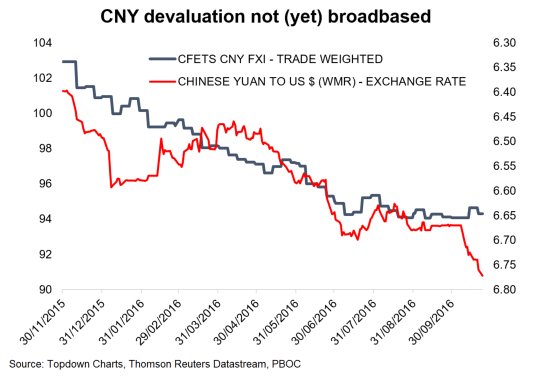

Despite the claims by Trump and Navarro, the Chinese yuan is not under-valued against the USD. As shown by this chart from Callum Thomas of Topdown Charts, the decline in CNYUSD is mostly attributable to USD strength (red line). CNY has been relatively steady against its CFETS currency basket (blue line).

If the US were to pressure China on trade, Beijing would react badly. Ian Bremmer of Eurasia Group believes that internal political pressures gives Xi Jinping little room to maneuver:

China’s scheduled leadership transition this fall will shape its political and economic trajectory for a decade or more. The scale of elite turnover before, during, and after the upcoming 19th Party Congress, combined with the divisive political environment that President Xi has fostered, will make this transition one of the most complex events since the beginning of China’s reform era.

Two risks flow from the upcoming power consolidation. First, because Xi will be extremely sensitive to external challenges to his country’s interests at a time when all eyes are on his leadership, the Chinese president will be more likely than ever to respond forcefully to foreign policy challenges. Spikes in US-China tensions are the likely outcome. Second, by prioritizing stability over difficult policy choices in the run-up to the party congress, Xi may unwittingly increase the chances of significant policy failures.

Xi cannot be seen to appear weak and therefore he will not tolerate any challenges. Notwithstanding issues like Taiwan and the South China Sea, which could be geopolitical flashpoints in 2017, expect economic challenges on trade to be met with resolve.

Xi’s sense that he will have to respond resolutely to any foreign challenge to national interests—in a year during which popular and elite perception of his leadership matter more than ever—means foreign policy tensions will escalate. At the least, Xi will view any external challenge as an unwelcome distraction from his focus on domestic political machinations. At worst, he will fear such threats could undermine his standing at home. Consequently, the president is likely to react more forcefully than his potential challengers expect. And unfortunately for global stability, the list of triggers that could rattle the president is long: a newly-empowered Trump and his China policy, Taiwan, Hong Kong, North Korea, as well as the East and South China Seas.

That’s how trade wars and hard landings can happen:

The intense focus on domestic stability means Xi may well overreact or stumble over any sign of economic trouble. This risk could take the form of a re-inflation of asset bubbles to boost domestic growth, or a substantial ramp-up in capital controls—either move would rattle foreign investors and international markets. Whatever form it takes, any misstep by Xi would provoke global economic volatility.

In case you didn’t get that, “global economic volatility” is code for “rising risk of a synchronized global recession”.

What happens in a trade war?

Should the Trump administration label China a currency manipulator and impose tariffs on Chinese exports, China will respond forcefully. The Petersen Institute modeled what would happen in a full-blown trade war. US GDP would be flat for two years – and those are just the first order effects.

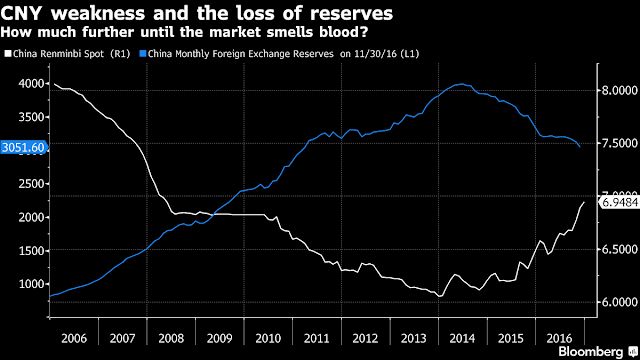

The first shot in a trade war would also give the green light for the PBoC to weaken the CNY (what else do they have to lose?) in response. Already, China is struggling with capital flight. A collapsing CNYUSD exchange rate risks a disorderly hemorrhage of China’s foreign exchange reserves. In addition, China’s newly announced regulatory changes to stem capital flight does not exactly inspire confidence.

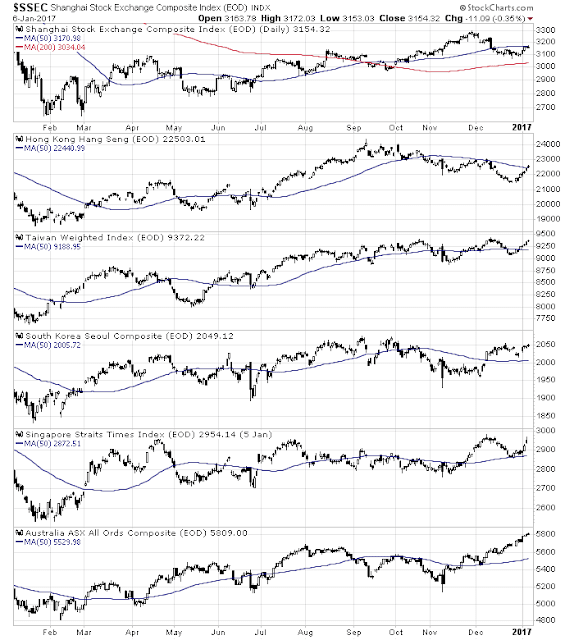

If the Chinese economy were to tank, the collateral damage would first be felt among China’s major Asian trading partners, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. The import of capital goods from Europe, most notably Germany, would fall. The failure of German exports, which has been the growth engine of the Europe, would weaken the already fragile eurozone financial system, whose leverage problems have not been solved since the last crisis. The problems of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena will be a tempest in a teapot compared to the problems that the European financial system will have to face.

Moderating influences on trade

At this point, the US induced China slowdown scenario is just a speculative scenario. It’s impossible to know how the Trump administration will actually act when it assumes power.

On one hand, Trump has flip-flopped on many issues over the years, but he has stuck to the assertion that China has been an unfair trader. The prospect of a protectionist US government will undoubtedly give the market jitters.

On the other hand, there are signs that there are moderating influences within the Trump administration on trade. Politico reported that Wilbur Ross was a Sinophile before he got the nomination to become Commerce Secretary. Ross could very well be a moderating influence on trade within the Trump administration.

I think the China-bashing is wildly overdone in this country,” said Ross in one CNBC interview, a statement that would have come across as a veiled swipe at Trump if he hadn’t made it in 2012. “The reality is that if something were to happen that cost China jobs, like if they upwardly revalued the currency a lot, those jobs aren’t going to come back to the U.S., they would go to Vietnam, they would go to Thailand, they would go to whatever country was the lowest cost, so it’s a fiction on both sides that those jobs will come back.”

Asked about outsourcing four years earlier by Profit Magazine, he said, “China has become the whipping boy in the U.S., just as Japan was some 15 years ago. This certainly is intellectually wrong.”

And in May, Ross, 79, explicitly departed from his future boss on a flashpoint in international trade, noting that China’s currency is in fact overvalued, not undervalued as Trump had been claiming on the campaign trail. “I disagree with my friend Mr. Trump in that particular regard,” he told Bloomberg.

More importantly, the New York Times reported that Trump`s son-in-law Jared Kushner has been pursuing a property development deal of a NYC building at 666 Fifth Avenue with Anbang Insurance, a Chinese financial conglomerate with uncertain ownership. Such relationships could color the administration`s views on trade with China as Kushner is expected to have an important unofficial voice in foreign affairs.

Indeed, despite a lack of foreign policy experience, Mr. Kushner is emerging as an important figure at a crucial moment for some of America’s most complicated diplomatic relationships. Such is his influence in the geopolitical realm that transition officials have told the Obama White House that foreign policy matters that need to be brought to Mr. Trump’s attention should be relayed through his son-in-law, according to a person close to the transition and a government official with direct knowledge of the arrangement.

So when the Chinese ambassador to the United States called the White House in early December to express what one official called China’s “deep displeasure” at Mr. Trump’s break with longstanding diplomatic tradition by speaking by phone with the president of Taiwan, the White House did not call the president-elect’s national security team. Instead, it relayed that information through Mr. Kushner, whose company was not only in the midst of discussions with Anbang but also has Chinese investors.

Notwithstanding how Trump and Kushner negotiate the delicate conflicts of interest issues, Trump himself has financial interests that are tied to Chinese state owned enterprises:

On China, Mr. Trump has talked a tough game, accusing Beijing of currency manipulation and raising the possibility of a trade war. But whether that is only a negotiating tactic remains to be seen. The president-elect has his own financial entanglements with China: He owns a 30 percent stake in a partnership that owes roughly $950 million to a group of lenders that includes the Bank of China, and one of his biggest tenants at Trump Tower is another state-owned bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

The trade policy situation can only be described as fluid. I am watching how the Asian stock markets as my canaries in the coalmine. So far, they are behaving well as the stock indices of China’s major trading partners remain above their 50 day moving averages.

The week ahead: Watch for volatility

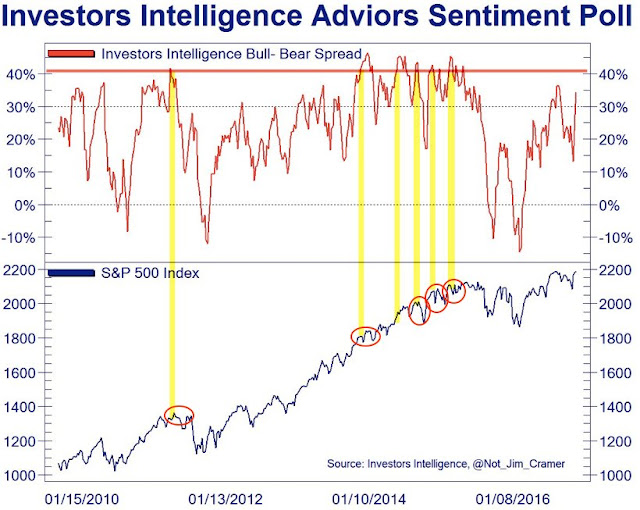

Looking to the week ahead, the Dow came within a hair of 20,000 at 19,999.63 and pulled back. Sentiment readings are overly bullish, which suggests a period of consolidation or pullback is ahead (via Urban Carmel).

Bloomberg reports that the latest readings from BAML’s funds flow analysis shows that nearly $70 billion have poured into equities since the election.

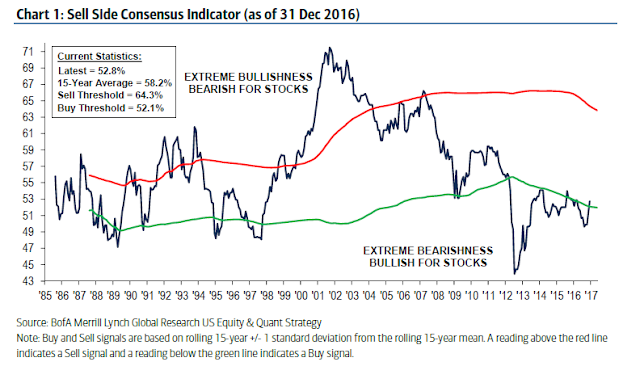

The BAML Sell Side Indicator, which measures the bullishness of Street strategists on stocks, has spiked from a contrarian buy signal into neutral territory.

Equally worrisome are the action of insiders. The latest update from Barron’s shows that this group of “smart investors” have moved into sell mode. Readings of insider activity tend to be noisy, but this latest data point represents another headwind for the bulls.

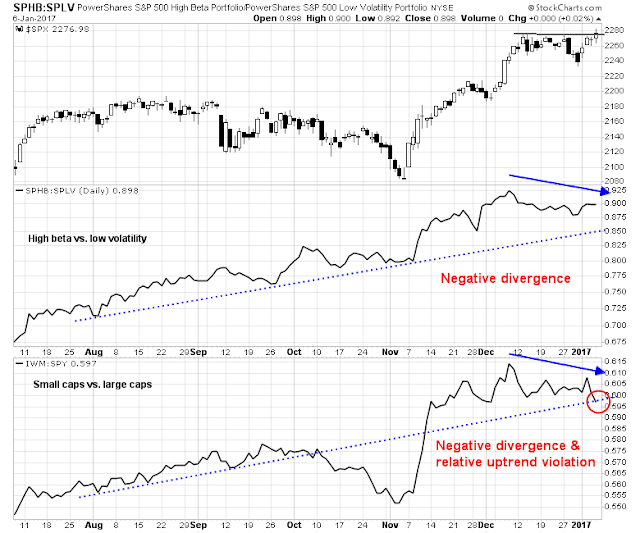

Measures of risk appetite are equally disturbing. Even as the market tested resistance at fresh highs on Friday, the chart below shows that risk appetite metrics were falling. The ratio of high beta to low volatility stocks (middle panel) was making a pattern of lower lows and lower highs. The relative performance of small caps to large caps (bottom panel) had violated its relative uptrend in addition to displaying a negative divergence condition.

When I put it all together, near-term upside potential is probably limited. A more likely outcome would be a period of sideways consolidation or pullback. My inner investor remains constructive on stocks, though he is nervously monitoring how the trade positions of the new Trump administration evolves.

My inner trader has taken a small short position in stocks. He waiting for the inevitable end of the Trump honeymoon. Wait for potential fireworks from the Trump press conference on Wednesday.

Disclosure: Long SPXU