President Trump has threatened to impose a State of Emergency in order to get his Wall built. Can he do that? Analysis from The Economist indicates that there is historical precedence for such actions:

Presidents do have wide discretion to declare national emergencies and take unilateral action for which they ordinarily need legislative approval. A “latitude”, John Locke wrote in 1689 (and his writings influenced the US constitution), must be “left to the executive power, to do many things of choice which the laws do not prescribe” since the legislature is often “too slow” in an emergency. American presidents have, for example, suspended the constitutional guarantee of habeas corpus (Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War), forced people of Japanese descent into internment camps (Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the second world war) and imposed warrantless surveillance on Americans (George W. Bush after the September 11th attacks). With some notable exceptions, including when the Supreme Court baulked at Harry Truman’s seizure of steel mills during the Korean War, the judiciary has usually blessed these actions. In addition, Congress has passed dozens of laws—New York University law school’s Brennan Centre for Justice has catalogued 123—giving presidents specific powers during emergencies.

Once Trump has opened has opened the door to a State of Emergency, what happens next? What does that mean for the markets?

Few limits on emergency powers

The question of the wisdom of these decisions is beyond my pay grade, but I can shed some light on the constitutional, legal, and market implications of the declaration of a State of Emergency. Elizabeth Goitein wrote in an article in The Atlantic and concluded there are surprising few constraints on the President to declare a State of Emergency:

Unlike the modern constitutions of many other countries, which specify when and how a state of emergency may be declared and which rights may be suspended, the U.S. Constitution itself includes no comprehensive separate regime for emergencies. Those few powers it does contain for dealing with certain urgent threats, it assigns to Congress, not the president. For instance, it lets Congress suspend the writ of habeas corpus—that is, allow government officials to imprison people without judicial review—“when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it” and “provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.”

Nonetheless, some legal scholars believe that the Constitution gives the president inherent emergency powers by making him commander in chief of the armed forces, or by vesting in him a broad, undefined “executive Power.” At key points in American history, presidents have cited inherent constitutional powers when taking drastic actions that were not authorized—or, in some cases, were explicitly prohibited—by Congress. Notorious examples include Franklin D. Roosevelt’s internment of U.S. citizens and residents of Japanese descent during World War II and George W. Bush’s programs of warrantless wiretapping and torture after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Abraham Lincoln conceded that his unilateral suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War was constitutionally questionable, but defended it as necessary to preserve the Union.

Congress passed the National Emergencies Act in 1976, but that law has largely failed in reining in Presidential powers:

Under this law, the president still has complete discretion to issue an emergency declaration—but he must specify in the declaration which powers he intends to use, issue public updates if he decides to invoke additional powers, and report to Congress on the government’s emergency-related expenditures every six months. The state of emergency expires after a year unless the president renews it, and the Senate and the House must meet every six months while the emergency is in effect “to consider a vote” on termination.

By any objective measure, the law has failed. Thirty states of emergency are in effect today—several times more than when the act was passed. Most have been renewed for years on end. And during the 40 years the law has been in place, Congress has not met even once, let alone every six months, to vote on whether to end them.

As a result, the president has access to emergency powers contained in 123 statutory provisions, as recently calculated by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law, where I work. These laws address a broad range of matters, from military composition to agricultural exports to public contracts. For the most part, the president is free to use any of them; the National Emergencies Act doesn’t require that the powers invoked relate to the nature of the emergency. Even if the crisis at hand is, say, a nationwide crop blight, the president may activate the law that allows the secretary of transportation to requisition any privately owned vessel at sea. Many other laws permit the executive branch to take extraordinary action under specified conditions, such as war and domestic upheaval, regardless of whether a national emergency has been declared.

In addition to the well-known examples of Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, FDR’s imprisonment of Japanese citizens, and George W. Bush’s warrantless wiretapping and torture, the government can in effect destroy an individual’s livelihood under these provisions:

President George W. Bush took matters a giant step further after 9/11. His Executive Order 13224 prohibited transactions not just with any suspected foreign terrorists, but with any foreigner or any U.S. citizen suspected of providing them with support. Once a person is “designated” under the order, no American can legally give him a job, rent him an apartment, provide him with medical services, or even sell him a loaf of bread unless the government grants a license to allow the transaction. The patriot Act gave the order more muscle, allowing the government to trigger these consequences merely by opening an investigation into whether a person or group should be designated.Designations under Executive Order 13224 are opaque and extremely difficult to challenge. The government needs only a “reasonable basis” for believing that someone is involved with or supports terrorism in order to designate him. The target is generally given no advance notice and no hearing. He may request reconsideration and submit evidence on his behalf, but the government faces no deadline to respond. Moreover, the evidence against the target is typically classified, which means he is not allowed to see it. He can try to challenge the action in court, but his chances of success are minimal, as most judges defer to the government’s assessment of its own evidence.

Here is just one example of how a case of mistaken identity devastated someone’s life:

For instance, two months after 9/11, the Treasury Department designated Garad Jama, a Somalian-born American, based on an erroneous determination that his money-wiring business was part of a terror-financing network. Jama’s office was shut down and his bank account frozen. News outlets described him as a suspected terrorist. For months, Jama tried to gain a hearing with the government to establish his innocence and, in the meantime, obtain the government’s permission to get a job and pay his lawyer. Only after he filed a lawsuit did the government allow him to work as a grocery-store cashier and pay his living expenses. It was several more months before the government reversed his designation and unfroze his assets. By then he had lost his business, and the stigma of having been publicly labeled a terrorist supporter continued to follow him and his family.

Presidents can even send troops into the streets:

Presidents have wielded the Insurrection Act under a range of circumstances. Dwight Eisenhower used it in 1957 when he sent troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce school desegregation. George H. W. Bush employed it in 1992 to help stop the riots that erupted in Los Angeles after the verdict in the Rodney King case. George W. Bush considered invoking it to help restore public order after Hurricane Katrina, but opted against it when the governor of Louisiana resisted federal control over the state’s National Guard. While controversy surrounded all these examples, none suggests obvious overreach.

And yet the potential misuses of the act are legion. When Chicago experienced a spike in homicides in 2017, Trump tweeted that the city must “fix the horrible ‘carnage’ ” or he would “send in the Feds!” To carry out this threat, the president could declare a particular street gang—say, MS‑13—to be an “unlawful combination” and then send troops to the nation’s cities to police the streets. He could characterize sanctuary cities—cities that refuse to provide assistance to immigration-enforcement officials—as “conspiracies” against federal authorities, and order the military to enforce immigration laws in those places. Conjuring the specter of “liberal mobs,” he could send troops to suppress alleged rioting at the fringes of anti-Trump protests.

Now imagine Trump in charge of the government under a State of Emergency. If you are a Trump supporter, imagine Hillary Clinton as POTUS declaring a State of Emergency.

P/E multiple contraction ahead?

Past Presidents who have declared States of Emergency have only done so under extraordinary circumstances, and they have shown respect for the Constitution. By contrast, Donald Trump was elected to be a disruptor, and he has shown little respect for Washington norms. As an example, Trump wanted his personal pilot to head the FAA, and he has a record of demanding personal loyalty instead of loyalty to upholding the Constitution.

I had written about the importance of institutions as a key ingredient for long-term growth (see How China and America could both lose Cold War 2.0). Josh Brown recently railed against the erosion of the rule of law:

When you hear an investor compare US, UK, German and Japanese stock market valuations with the countries that make up the Emerging Markets index, try to keep in mind the fact that the discounts of the latter are nearly always warranted. We can debate about the degree of cheapness in emerging Latin American or Asian stock markets – this is subjective. What is not up for debate is whether or not there ought to be a discount. Of course there needs to be.

And the reason why, very simply, is the presence of a rule of law that applies to everyone – or, at least, the perception of a rule of law. Shares of stocks are contracts; agreements between the owners of a business and those who manage it on behalf of those owners. And these contracted agreements – regarding the payment and allocation of cash flows, safeguarding of intellectual property, continuance of competitive business practices, respect for minority shareholders, etc – are sacrosanct.

The same could be said of the governance environment in which the companies operate. Investors need to feel that there is fairness and a set of rules that everyone must adhere to. No one would build a house on quicksand and no one would exchange currency for pieces of paper in an environment where legal protections no longer mattered.

This is the kind of behavior that investors find in emerging market countries. According to FactSet, US equities trade at a forward P/E of 15.1, which is just slightly above the historical 10-year average.

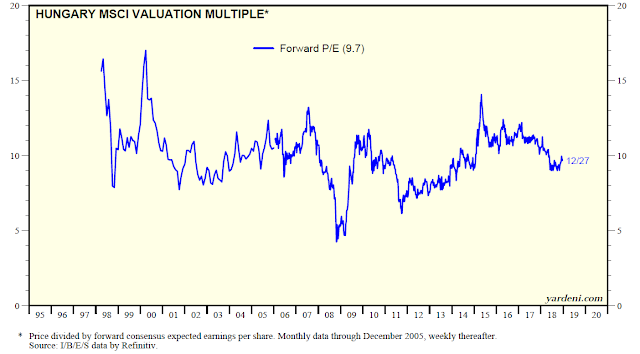

Compare this to the forward P/E of EM countries with executive power concentrated in autocrats and weak institutions. They mostly trade at single digit forward P/E multiples. Watch for the market to start pricing a political risk premium under a State of Emergency. Such a development would be equity and USD bearish, and gold bullish.

Here is Egypt.

Here is Hungary.

Russia, the home of the kleptocrats, trades at 4.6x forward earnings.

Turkey, which has been the bad boy of the markets, trades at 5.9x forward earnings and the historical average is under 10.

China trades at 10x forward, but the historical average is in the low teens.

For an explanation of why P/E ratios would deflate, imagine the following extreme scenario. Donald Trump declares himself President For Life. At what rate would you lend the US Treasury money for 10 years? The current rate of 2.7%? What would you demand? 4%? 7%? 10% or more? Add 3-5% for an equity risk premium over the 10-year Treasury yield, and invert the result. That’s how you approximate a target P/E ratio.

Supposing you decided that you would lend money to a Treasury controlled by Trump at a rate of 7%. Adding in an equity risk premium of 4% translates to a forward P/E of 9x earnings. If the SPX were to fall from 15x to 9x forward earnings, the index would fall to roughly 1600.

No doubt the Democrats will fight Trump’s powers through the Courts, but even if they were to succeed in restraining presidential powers, the process will take several months, and the markets will shoot first and ask questions later.

George Washington`s last stand

I close with a relatively obscure story from a key episode in American history. It was 1783. The Revolutionary War was over, but the country was bankrupt and the Continental Congress refused to pay the troops. Some of George Washington`s men had urged him to take command and rule as an undeclared king:

On March 15, 1783 the officers under George Washington’s command met to discuss a petition that called for them to mutiny due to Congress’ failure to provide them back pay and pensions for their service during the American Revolution. George Washington addressed the officers with a nine-page speech that sympathized with their demands but denounced their methods by which they proposed to achieve them.

Washington refused. It was a key moment in American history. He could have become President For Life, but he had too much respect for the institutions that he fought for. Go and read the foll account of Washington`s address to the troops.

To even imagine and write the words that “Donald Trump declares himself President For Life” because he wants to stop the flow of illegal aliens, drugs, criminals, and even people on the terrorist watch list across our southern border is irresponsible, divisive, and indicates you’ve been getting your opinions from too many anti-Trump sources. And, it does not lead to useful investing advice. Better to write an article about the effect on the markets if he declares the specific state of emergency being discussed.

You are obviously a Trump supporter. Can you imagine the following:

HRC won the election.

She declares a State of Emergency to ram through some initiative because of a budget impasse. Once she has cross that Rubicon, how much further is it to manufacture some crisis and declare herself President for Life?

Asking for a friend.

I appreciate Cam’s comments! Good job!

@ Brad

To second Cam’s answer, actually, it does lead to useful investing advice. Imagine you were in 1939 Germany, and someone told you to cash out of German stock market, which is not what Cam is saying, he is playing a hypothetical scenario. This is not being hysterical, just pointing out that Germany did happen.

So, telling it like it is, is useful advice. You don’t have to agree to it, but you can’t blanket statement and tell him he is being irresponsible And seeing the way Trump is going, I don’t believe Cam is at all far fetched with that Scenario. Just a counter point to your point. And, maybe you need to get your news from other than Faux News.

Also, will you feel ok if if HRC made up a Crisis and then declared an Emergency due to this made up crisis? Just wondering.

The key phrase is “he (Washington) had too much respect for the institutions that he fought for”. We now have a president that has not fought and has no respect for institutions, only motivated by his own ego.

Thanks Cam, great article.

President for life? Surely prison for life is a more plausible scenario! The Mueller inquiry is shaping up, and its possible Trump won’t complete his first term, never mind run for a second.

The good news is that this would likely be neutral or positive for the markets, The US was fine when Nixon was busy battling Watergate, and Belgium did great without any government at all for two years ten years ago…

Fantastic insight!

I think at this forum we should just focus on investing. Pls don’t dip into personal preference. Whatever happens in the future we can assess and adjust.

For a diversion, let’s see if the last man standing, i.e. the cloud-related software issues, can continue to stay at close to ATH. Their leader, MSFT, does not act well compared to the rest of the group. If AMZN also reports AWS numbers not as hot as before, then we will have a serious problem. That means big chunk of NDX growth is waning. Cloud is the only high growth area we have. I remember MU said not long ago that these big cloud companies suddenly reduce the order of their memory modules, saying they have too much inventory. What does this mean precisely?

It is not necessary to go to the “Trump as President for Life” thought experiment to see that a declaration of emergency–to get the wall built in this case–is a relatively minor use of this abuse compared with the examples you gave of Roosevelt, Kennedy and Bush. That Trump has no respect for anything is already evident. He has been restrained by the courts several times without “sending in the troops”. He is as much bluster and threat as he is imperious. He gets that much closer to full impeachement as the governement closing continues. It takes but 20 Republican Senators to join all the Dems. This while not likely is far from improbable. There are pretty good reason aside from Trump to account for an economic slow down world wide which reduces earnings and profits. rdmill

There is an old adage of investments. Buy at the sound of cannons and sell at the sound of trumpets. I am not sure of the origin of this, but it seems like politics rules geopolitical investment risk with a capital P.

Trumpism is no different and one would be cavalier of ignoring the risks that President Trump brings to the table.

In the world of investments, risk is omnipresent, rewards are nebulous. It is about control of risk, and politics is one type of risk, no question about it. Thanks Cam, for floating a Black Swan idea. War is one that keeps me up at night. America waged wars in 1991, 2001, one a decade, though the sample size of two is meaningless. That said, one may be around the corner.

I am still amazed that so many smart individuals still think (or hope) the Mueller inquiry will bear fruit. If the Mueller inquiry is thought of as a company, after using countless millions and almost two years and still nothing to show for the investigation. Shorting this company would be the most profitable strategy.

This is not not meant as political comment. I wonder are there any betting action on the Mueller investigation.